Disciple: Unburied History

How St. Mark’s, Huntersville, is honoring the lives and legacies of formerly enslaved people

By Summerlee Walter

Elizabeth McCoy—not her family surname, but the one she received from the people who once owned her—was better known as Lizzie. She might have been married to a man named Jim, or he might have been her older male relative. She had three children who preceded her in death, but there is no record either of her birth and death dates or her children’s. What we do know about Lizzie is filtered through the memories of Albert McCoy’s 12 children, who she raised as a free woman, and the inherited family stories their descendants still tell today. Some of those stories feature retellings of Lizzie’s own tales and so reveal something about the personality, wit and creativity of the woman who originally told them, although her voice is lost to history. We don’t even know by what name she would have preferred to be called, if she’d had the choice.

We know Lizzie and her contemporaries, Charles and Jim, existed because their names appear on the single marker in the McCoy Cemetery, established by the McCoy family during the 1840s and used for interments until the 1880s. The name as it appears in public listings, as the “McCoy Slave Cemetery,” is likely a misnomer, since most of the people buried there were probably free at the time of their deaths, but the history is murky. Of the unknown number of souls interred in the cemetery, we know only Lizzie, Charles and Jim because no individual markers survive, if they ever existed. Whatever might once have lovingly been placed there by family and friends—large rocks, pieces of crockery or wooden markers—has rotted away or been lost.

[Image: The 1928 marker placed by the McCoy family in the McCoy Cemetery shepherded by St. Mark's, Huntersville.]

The surviving marker was placed by the children of Albert McCoy in 1928, and in 1946, the family gave the property to St. Mark’s, Huntersville, in trust so the church could maintain it as a perpetual care cemetery. The bequest included “… a lot of 60 feet square and inside of which square is a stone and concrete monument erected by the said heirs of the late Albert McCoy as a memorial to the Negro slaves or servants of the family in gratitude of their loyal services, many of whom are buried on said plot.” The documentation from the time of the bequest does not do much to help pick apart the tangle of possible motives for such a donation: fond childhood memories, an urge toward restitution, gratitude, guilt, a sense of responsibility for ancestral actions, perhaps a bit of each.

Regardless of how the cemetery became what it is today, St. Mark’s, which has cared for the land during the past 75 years, recently began the process of learning more about the people buried there and trying to locate any living relatives, in order to invite them to help honor their memories. St. Mark’s parishioner David Fahey has done much of the research, which he recently shared as part of the remembrance and re-dedication service the church held on Juneteenth (June 19).

[Image: Bishop Jennifer Brooke-Davidson, the Rev. Canon Lindsey Ardrey, the Rev. Garry Edwards and the Rev. Canon Kathy Walker at the service of remembrance and re-dedication.]

READING BETWEEN THE LINES

Prior to 1870, no biographical data about enslaved people appeared on the census, but because they counted as three-fifths of a person when calculating representation in Congress, their identities were recorded in slave registers. Occasionally they also appeared in bills of sale or estate records as property. So far, Fahey has identified 8-10 people who might be buried in the cemetery. Judy, aged 17, appears in the McCoy papers at UNC-Charlotte on a bill of sale dated February 25, 1817. Marshall McCoy, Albert’s father, purchased her for $480. Jim appears in an 1830 purchase record, which lists him as 45 or 50 years old. He seems to appear again on the 1850 slave census, which lists eight enslaved people owned by Marshall McCoy, including a 70-year-old man. In 1854, Marshall died, and his estate was auctioned off. Listed on the record of sale are Boy Jas.; Amy; Charles, Ann and child; Ellen; Febe; Maiah; Calvin; and Jude. Fahey believes Charles is the same man who appears on the monument.

Reflecting on what he uncovered in the historical record, Fahey said, “There were little hints that indicated—and maybe it’s wishful thinking—but every once in a while you’d see something like a family sold together to the same [McCoy] family member. It seems like they didn’t want to sell them to strangers. It’s hard to tell if that was a coincidence or not, but most of [the enslaved people owned by Marshall] were purchased by family members.” For example, Judith and Pheby, possibly the same Jude and Febe listed in the estate sale, appear on the 1862 baptismal record of Hopewell Presbyterian Church as servants of Marshall’s widow and daughter.

The first census after emancipation lists James, aged 87; Elizabeth, aged 47; and Thomas, aged 17, as members of the McCoy household. James is probably the same Jim who appears in several other records and on the cemetery monument, but the 40-year age difference between he and Elizabeth calls into question their purported marriage. Jim appears one last time in an obituary in an 1877 edition of the “Charlotte Democrat,” which reported he lived with his former owners until his death, was buried by the family at his request, and was interred among a crowd of friends both Black and white. Whether or not the reality reflected the white newspaper writer’s account is lost to history, but the publication of Jim’s obituary does suggest he was a valued member of the community.

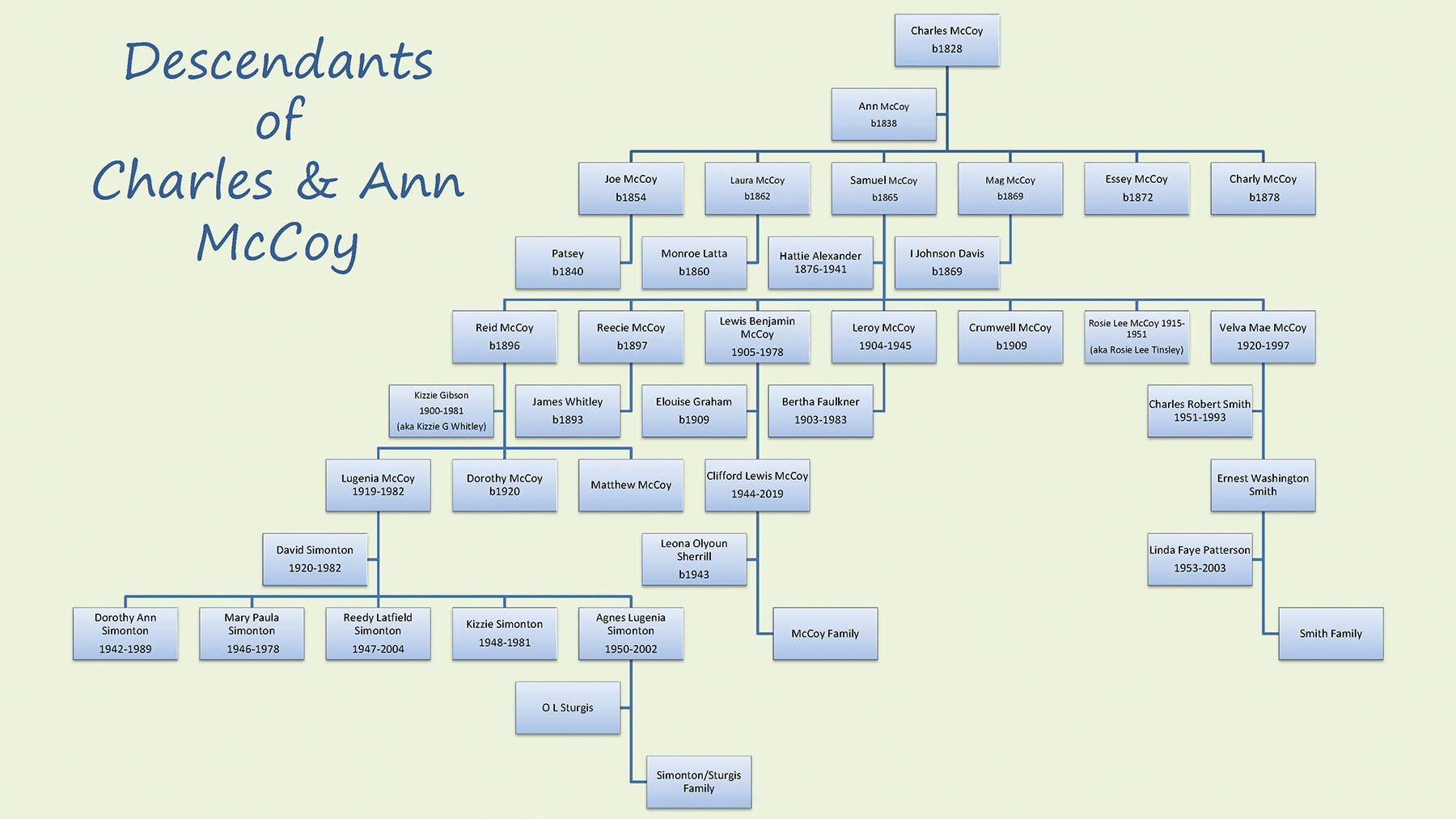

In the 1880 census, Lizy, now spelled differently, reappears in Albert’s household as a widow. New names also appear. Charles has a wife, Ann, and five children: Laura, Sam, Mag, Essey and Charly. Joe, aged 26, and his wife, Patsey, are also listed. Based on his age, Joe is likely the child of Charles and Ann listed in the 1855 estate sale. In 1883, Charles might have gotten remarried, to a woman named Harriet Allison. His son, Sam, married Hattie Alexander, in 1896. The 1900 census indicates Lizzie is still alive, and that is where the record of those who might be buried in the McCoy Cemetery stops.

Fahey has located the graves of several of Sam and Hattie’s children and possible grandchildren in other cemeteries throughout North Carolina. He has created a family tree to illustrate their lineage but has been unable to do the same for Lizzie or Jim. Lizzie, however, lives on in the stories passed down through generations of McCoy children, including the story of “The Old Bad Man,” as retold by Arrington McCoy, the great-granddaughter of Albert’s son, Thomas. In 2014, St. Mark’s parishioner Elena Michel illustrated and published the story as a free pamphlet available for download on St. Mark’s website.

[Image: Sam and Hattie McCoy’s family tree. By David Fahey]

MAINTAINING HISTORY

According to St. Mark’s website, the McCoy Cemetery includes many features common to cemeteries where enslaved or formerly enslaved people are buried. Periwinkle was used as ground cover because it is easier to sow and maintain than grass. Fieldstones were placed in lieu of permanent grave markers. People are interred in an east-west burial pattern, either so they were buried facing east toward their ancestral homelands or so those who were Christian were buried facing the sunrise in preparation for the day of resurrection.

Since the cemetery came under St. Mark’s care in 1946, the area surrounding the property has changed. The cemetery, which is not attached to the church grounds, now sits in the middle of a county land conservancy, so the congregation is somewhat limited in what they can do to mark or update the site. During the 1990s, a St. Mark’s youth, for his Eagle Scout project, removed an old, unattractive chain link security fence and build a stacked split rail fence in its place. Time took its toll, however, and replacement rails of the type used in the initial construction are no longer available. This spring, Fahey removed what remained of the fence and replaced it with corner split rail markers. The church also collaborated with Mecklenberg County and Latta Place Historic Site to replace a dirt path covered in pine needles—a fire hazard during controlled burns—with a gravel pathway. They continue to work together to find a balance between access to the cemetery and conservation of the overall land area.

Fahey is working on changing the public name of the cemetery to something more accurate than the current Google listing that identifies it as the “McCoy Slave Cemetery.” The marker donated by the McCoy family, which reads “Erected by Albert McCoy’s children to his slaves, Uncle Jim & his wife, Lizzie, Uncle Charles & family,” is itself probably inaccurate, since Fahey doubts both that Albert ever owned enslaved people and that Jim and Lizzie were married. Despite the limitations imposed by the passage of time, the vagaries of history and the fuzziness of generational memory, the people of St. Mark’s are committed to honoring the lives and the stories of the people whose final resting place is under their care.

“The McCoy Slave Cemetery being entrusted to St Mark’s…is a true testament of a dark side of our country’s history, joined together with a McCoy family showing a form of warmth and kindness to a people who were mistreated,” the Rev. Garry Edwards, rector of St. Mark’s, said. “As the first rector of color at St. Mark’s, I found it not only imperative but almost obligatory to make sure the families laid to rest in that hallowed ground be always remembered and loved as Jesus Christ taught in ‘loving one another as he loved us.’ A remembrance service was only a small but fitting form to remind us we must never forget.

“Choosing Juneteenth as that day of remembrance not only remembered those here laid to rest, at this cemetery, but all enslaved people who endured such cruelty to help make this country what it is today. Also as part of our diocesan mission, the service recognized the struggle of the people of color in our communities through reconciliation and repatriation.

“I leave us with a quote from a fellow Barbadian like myself and vice-chancellor of University of the West Indies, Dr. Hillary Beckles, who said, ‘Reparative justice is not about Black people standing on the street corners expecting charities from white folks, this is about building of bridges across lines of moral justice.’”

LIZZIE'S STORIES

LIZZIE'S STORIES

“The Old Bad Man” is a tale of a young boy whose three brave dogs escape the family’s smokehouse to find and rescue the boy after he is captured by the titular villain while on his way to the mill. A retelling of the story by Arrington McCoy, the great-granddaughter of Albert’s son, Thomas, is available as a free download, courtesy of St. Mark’s. Elena Michel provided the illustrations and editing. Additional information about the McCoy Cemetery, including information about booking a tour, is available at the same link.

Summerlee Walter is the communications coordinator for the Diocese of North Carolina.

Tags: North Carolina Disciple / Racial Reckoning, Justice & Healing / Historiographer's Welcome